Back Problems in IT Professionals: Causes, Consequences, and Preventive Strategies

The rapid advancement of information technologies and the growing demand for digital infrastructure have led to a significant expansion of the IT sector. Professionals in this field frequently engage in prolonged periods of sedentary work, often in suboptimal ergonomic conditions. As a result, musculoskeletal disorders—particularly those affecting the back—have become increasingly prevalent among IT specialists.

Back pain is currently recognized as one of the most common occupational health issues worldwide, with the Global Burden of Disease study identifying it as a leading cause of disability. Among office workers, and especially those in the technology sector, the prevalence of lower and upper back pain is disproportionately high due to the nature of their daily tasks: prolonged sitting, repetitive computer use, and limited physical activity.

Despite its frequency, back pain is often underestimated until it significantly interferes with daily functioning and productivity. For IT professionals, chronic discomfort or restricted mobility can lead not only to a decline in quality of life but also to diminished work performance, increased absenteeism, and higher healthcare costs.

This article explores the structural and functional aspects of the spine, common types of back problems encountered by IT workers, occupational risk factors, and evidence-based strategies for prevention and management. The goal is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the issue and promote proactive measures to safeguard spinal health in technology-oriented work environments.

Structure and Function of the Spine

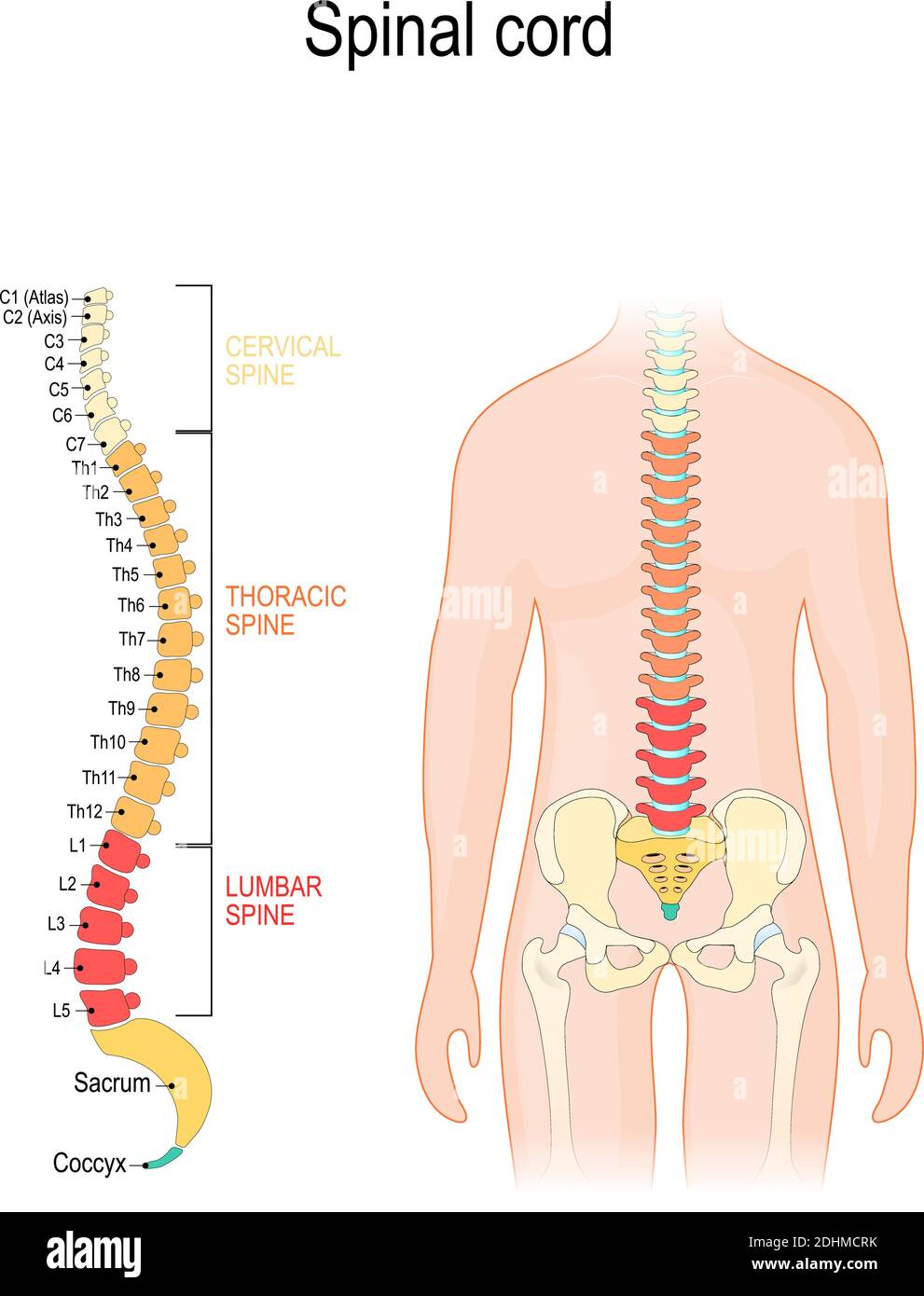

The human spine is a complex anatomical structure composed of 33 vertebrae, intervertebral discs, ligaments, and supporting musculature. It is divided into five regions: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal. Each region has distinct structural and functional characteristics that contribute to posture, mobility, and protection of the central nervous system.

At its core, the spine serves three primary functions:

- Structural support – It provides the main framework that supports the body’s weight and maintains upright posture.

- Mobility and flexibility – It allows for a wide range of movements, including bending, twisting, and rotation.

- Protection – It encases the spinal cord and serves as a conduit for nerve signals between the brain and the rest of the body.

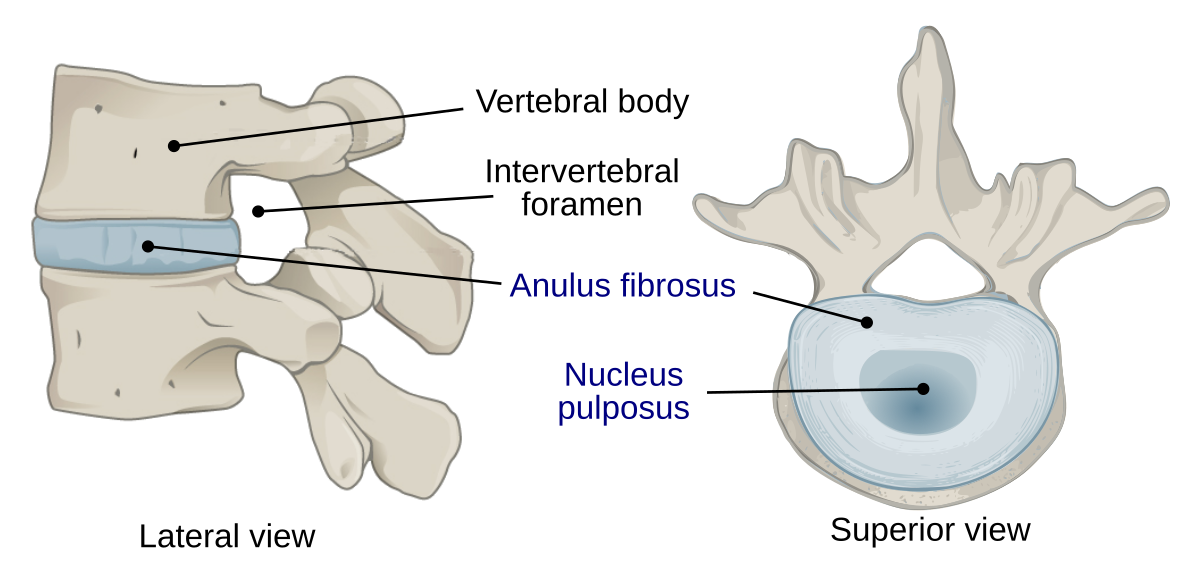

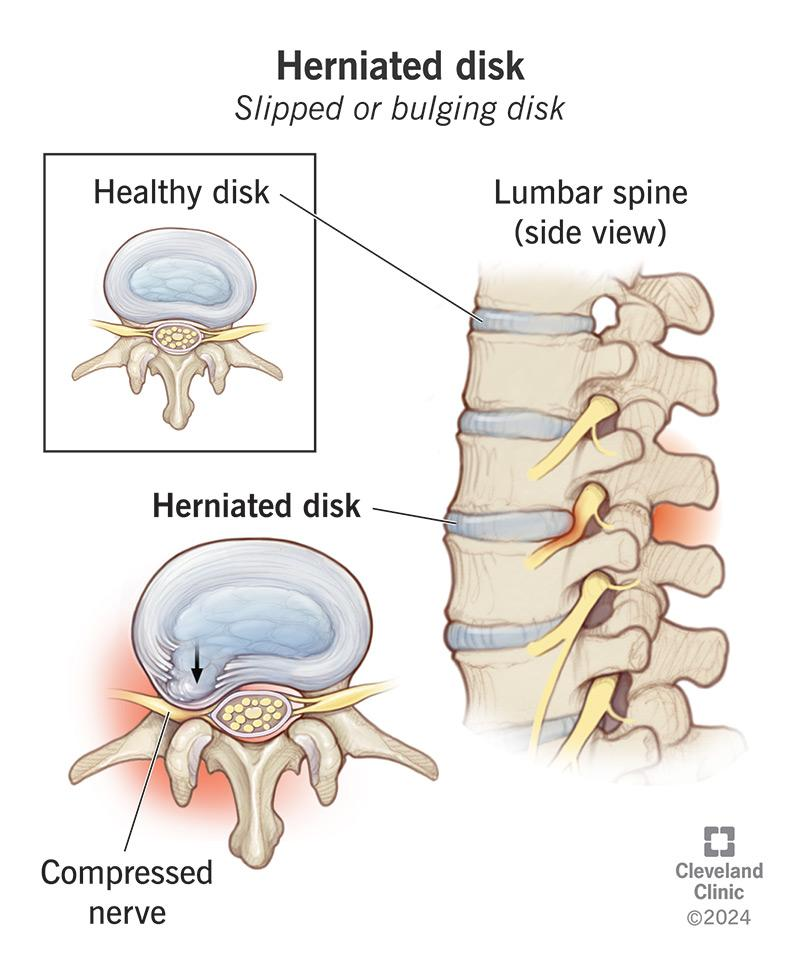

Intervertebral discs, located between each vertebra, act as shock absorbers and help maintain spinal flexibility. These discs consist of a tough outer ring (annulus fibrosus) and a gel-like inner core (nucleus pulposus). With prolonged pressure—especially from sustained sitting—these discs may become compressed, dehydrated, or herniated, leading to nerve irritation and pain.

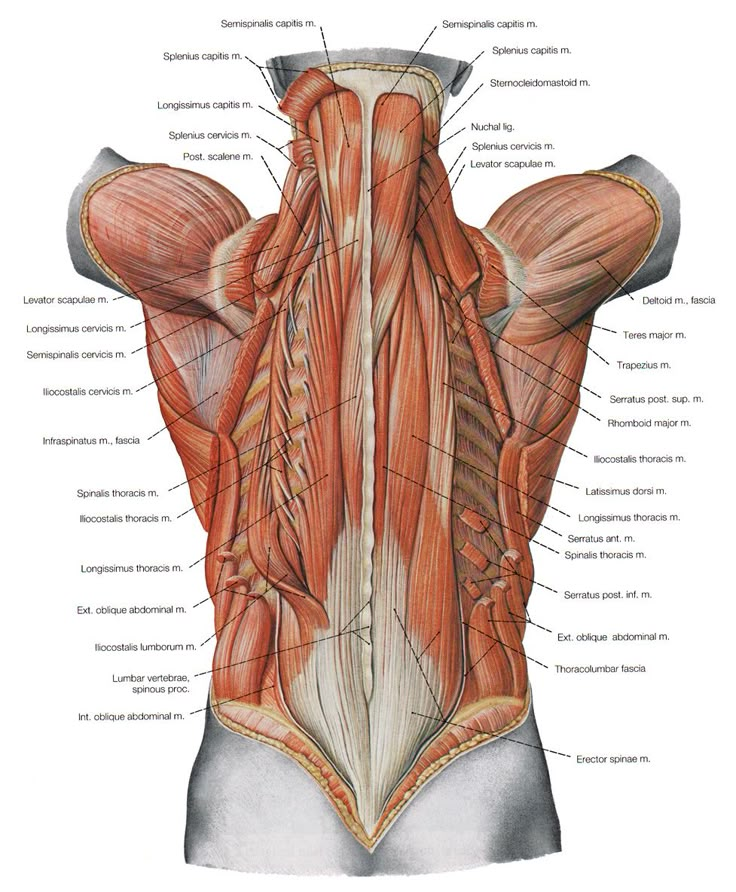

The muscles of the back play a crucial role in maintaining posture, enabling movement, and stabilizing the spine during both dynamic and static activities. They are typically categorized into three layers: superficial, intermediate, and deep. The superficial muscles, such as the trapezius and latissimus dorsi, primarily control movements of the shoulder and upper limb. The intermediate muscles, including the serratus posterior superior and inferior, assist with respiration. Most critical for spinal health are the deep (intrinsic) muscles, notably the erector spinae, multifidus, and transversospinalis groups, which are directly responsible for spinal extension, rotation, and stabilization. In the context of sedentary IT work, prolonged static postures often lead to underactivation of these deep stabilizers and overstrain of superficial muscles. Over time, this imbalance can contribute to postural dysfunction, muscle fatigue, and chronic back pain. Strengthening and properly engaging these muscular structures are therefore essential components in both the prevention and rehabilitation of back disorders.

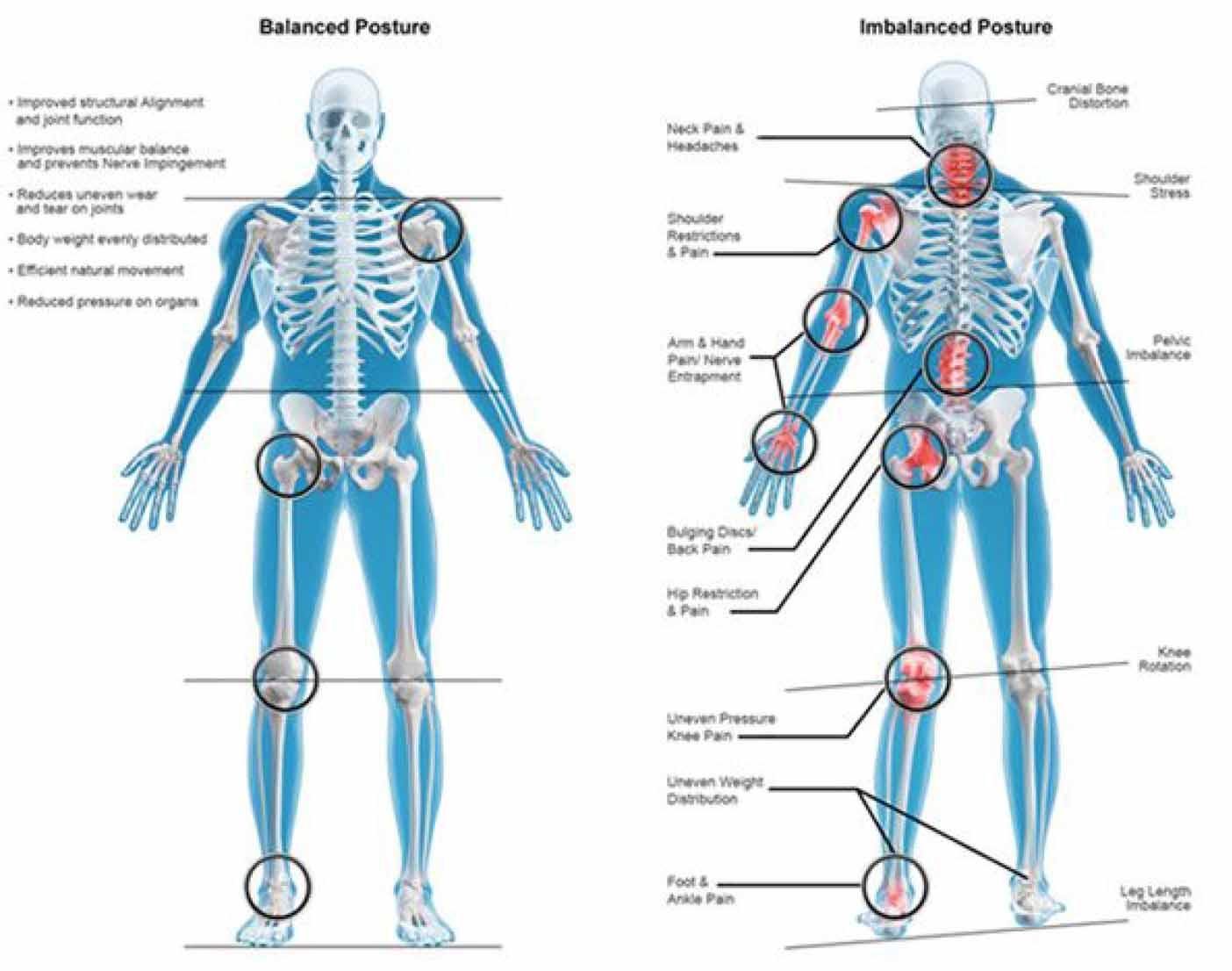

Proper spinal alignment is critical for distributing mechanical loads evenly and minimizing stress on joints and soft tissues. Imbalances in posture—such as slouching, forward head position, or prolonged static loading—can lead to muscular fatigue, ligament strain, and degenerative changes over time. Understanding the normal biomechanics of the spine is essential in recognizing how modern work habits, particularly in IT settings, can disrupt spinal health and contribute to back disorders.

Common Types of Back Problems in IT Professionals

IT professionals are particularly susceptible to a range of back problems due to prolonged sedentary behavior, suboptimal workstation setups, and insufficient physical activity. The most commonly observed conditions include:

- Muscular Strain and Imbalance

Prolonged static sitting and repetitive movements often result in muscle fatigue and imbalances. Typically, the deep stabilizing muscles become weakened, while superficial muscles such as the trapezius or lumbar extensors are overworked. This imbalance contributes to discomfort, reduced range of motion, and poor postural control.

- Herniated Discs

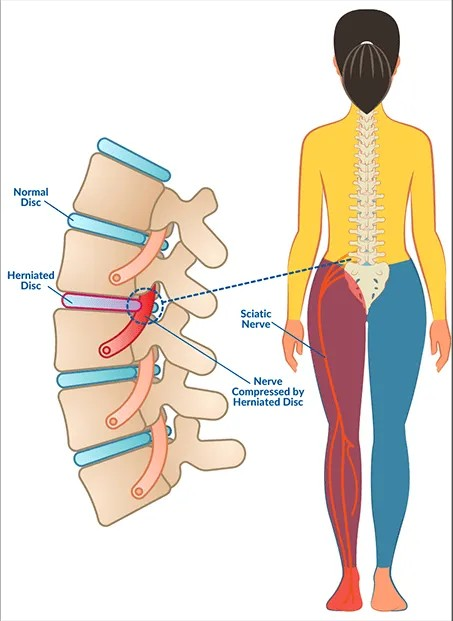

Sustained flexion of the lumbar spine—commonly caused by slouched sitting—places excessive pressure on the intervertebral discs, particularly in the lower back. Over time, the inner core of the disc (nucleus pulposus) may protrude through the outer layer (annulus fibrosus), irritating nearby nerves and leading to symptoms such as lower back pain, numbness, or radiating leg pain (sciatica).

- Postural Syndrome

Poor ergonomics and habitual poor posture can lead to a condition known as postural syndrome. It is characterized by adaptive shortening of certain muscle groups (e.g., hip flexors, pectorals) and weakening of others (e.g., gluteals, deep neck flexors). Common visual signs include forward head posture, rounded shoulders, and anterior pelvic tilt, all of which place additional mechanical stress on the spine.

- Sciatica

Sciatica refers to irritation or compression of the sciatic nerve, typically due to disc herniation or muscle tightness (such as piriformis syndrome). It presents as sharp or burning pain radiating from the lower back down the leg, often accompanied by tingling or weakness. Prolonged sitting, especially in a poor position, can exacerbate the condition.

- Chronic Lower Back Pain (CLBP)

Chronic lower back pain, defined as pain lasting longer than 12 weeks, is often multifactorial in IT professionals. It may result from a combination of mechanical stress, poor muscular support, and psychosocial factors such as job stress. Over time, it can significantly impair both work performance and quality of life.

- Upper Back and Neck Pain

Improper monitor positioning and prolonged forward head posture strain the cervical spine and associated musculature. This often leads to tension in the upper trapezius, levator scapulae, and suboccipital muscles. Symptoms may include stiffness, dull aching, and tension headaches, especially after long hours at the workstation.

Contributing Factors in IT Work

Back problems among IT professionals are rarely the result of a single cause; rather, they develop from a combination of occupational, environmental, and behavioral factors that exert continuous stress on the musculoskeletal system. The most significant contributors include:

- Prolonged Sedentary Behavior

IT work is predominantly desk-bound, often requiring individuals to remain seated for extended periods without adequate movement. Sustained sitting leads to static loading of spinal structures, reduced intervertebral disc nutrition, and weakening of the postural muscles, all of which increase the risk of both acute and chronic back conditions.

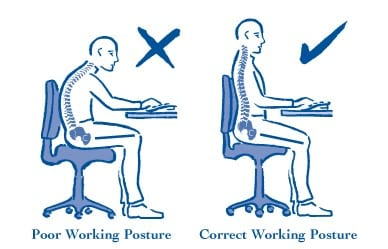

- Inadequate Ergonomic Setup

Improperly designed workstations are a major factor in the development of back pain. Chairs lacking lumbar support, desks at incorrect heights, and poorly positioned monitors force the spine into non-neutral alignments. Over time, these misalignments contribute to muscle imbalances, joint stress, and postural dysfunction.

- Physical Inactivity

The demanding schedules of IT professionals often result in reduced engagement in regular physical exercise. Without adequate muscular conditioning—especially in the core and back—there is insufficient support for the spine during prolonged sitting, increasing the likelihood of strain and fatigue.

- Repetitive Motions and Static Postures

While not typically physically intense, IT work involves repetitive hand and arm movements, particularly during typing or mouse use. Simultaneously, static postures maintained for long durations reduce blood flow to the back muscles and ligaments, making them more prone to injury.

- Occupational Stress and Mental Load

High cognitive demands, tight deadlines, and prolonged screen exposure can lead to increased muscle tension, particularly in the neck and shoulders. Chronic psychological stress has also been associated with heightened pain perception and delayed recovery from musculoskeletal injuries.

- Poor Work Habits and Lack of Awareness

Many IT professionals are unaware of proper sitting techniques or the importance of taking regular breaks. Habitual slouching, leaning forward, or using makeshift furniture at home offices can gradually lead to spinal strain, even in otherwise healthy individuals.

Impact on Quality of Life and Work Performance

| Impact Area | Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Function | Pain acts as a distraction, consuming mental resources | Reduced focus, slower problem-solving, increased error rates |

| Physical Performance | Musculoskeletal discomfort leads to fatigue | Decreased sitting endurance, frequent breaks needed, reduced workday productivity |

| Attendance & Productivity | Leading cause of work absences | Missed deadlines, disrupted team collaboration, "presenteeism" issues |

| Quality of Life | Pain extends beyond workplace | Limited physical activity, poor sleep quality, reduced social participation |

| Long-Term Implications | Progressive conditions may worsen over time | Potential for career limitations, degenerative conditions, nerve compression syndromes |

Conclusion

Back problems are a pervasive and often underestimated occupational hazard among IT professionals. The combination of prolonged sedentary behavior, inadequate ergonomic practices, and high cognitive demands places continuous stress on the spine and its supporting structures. Left unaddressed, these issues can lead to chronic pain, reduced work performance, and long-term health consequences that extend beyond the workplace.

Proactive intervention is essential. Implementing ergonomic improvements, encouraging regular movement, and promoting awareness of musculoskeletal health can significantly reduce the incidence and severity of back-related conditions. Employers and professionals alike must recognize the importance of integrating spinal health into workplace culture and daily routines.

This article is part of a larger initiative to promote comprehensive health awareness among cybersecurity and IT professionals. Our "Cybersecurity and Health: A Medical Guide for Professionals"—developed with the participation of medical experts and grounded in evidence-based medicine—covers the most common work-related health conditions in the field, including cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, neurological, and psychological concerns. It offers accessible explanations, practical recommendations, and scientifically validated strategies tailored specifically to the demands of cybersecurity and technology-focused roles.

Maintaining a healthy back is not only a matter of comfort but a fundamental aspect of long-term professional sustainability. By addressing these challenges with knowledge and intention, IT professionals can safeguard both their health and their performance.